The red inscription reads: “To be shot to death like wary dogs."

This kind of verdict was often heard in the court when innocent people, public figures and artists were executed by the Soviet Regime.” Welcome to the Red Terror exhibition.

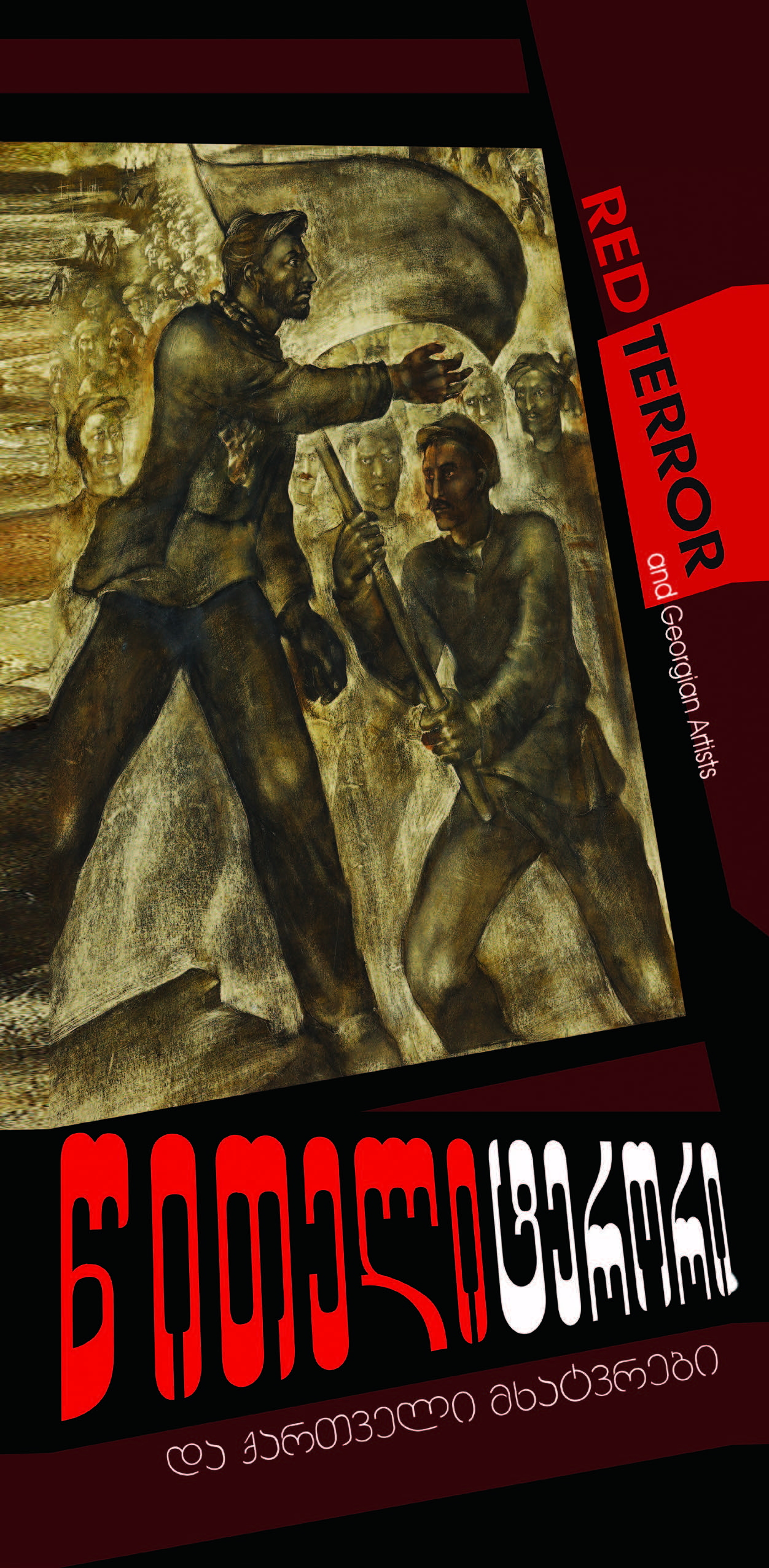

There are many names of Georgian artists, both contemporary and from the previous century, that are known internationally, yet there are many that have been in the shadows for years, forgotten as a result of Soviet rule. To remember and reintroduce the great representatives of Georgian art of the 1920s-40s, the Georgian National Museum for the first time presents the exhibition ‘Red Terror and Georgian Artists.’

The mass repressions known as the “Red Terror,” a powerful weapon directed towards total control, touched upon all layers and ages of society. The mass repressions hit both Georgian and foreign artists living in Georgia, whose creative and public activities had them standing as the vanguard of the country’s art processes. Great Georgian artists such as Petre Otskheli, Dimitri Shevadnadze and Vakhtang Kotetishvili fell victim to the Soviet rule and were shot for their work. These are artists who stood out for their individuality and courage, and distinct styles and ideas that were not acceptable to the Soviet authorities. Foreign artists who lived and worked in Georgia, Henryk Hryniewski and Richard Sommer, were accused of either counterrevolutionary activities or espionage and were executed like their Georgian counterparts, while Kiril Zdanevich, Ivane Pataridze and Vasily Shukhaev spent years in expatriation. Ria Mikadze and Nino Zaalishvili were charged as “family members of public enemies.” People saw the repressions take everything they had, sometimes even their lives. Those who survived execution or expatriation were forced to live in conditions of limited freedom of expression and their creative life suffered under Tsarist and later Communist Russia.

The exhibition Red Terror and Georgian Artists represents the creativity of the repressed artists and the general atmosphere of 1930-40s Georgian art.

“The exhibition incorporates two parts. The first focuses on five artists that experienced the worst pressure and were shot,” Eka Kiknadze, the head of the National Gallery and organizer of the project, told GEORGIA TODAY. “The works of Dimitri Shevardnadze, Petre Otskheli, Vakhtang Kotetishvili, Richard Sommer and Henryk Hryniewski are being exhibited on the first floor. The second part of the display is devoted to Georgian artists of the 1920s-1940s. Through these works, we aim to show how the Soviet regime and its ideology influenced art. The exhibition clearly shows the transformation of the artists, how they worked before and after the severe repressions. The Red Terror was especially painful for the artists who worked in the 1910s and so were able to experience Georgia as an independent country with easy access to Europe, until they were separated from it by the Iron Curtain. When the Bolsheviks came to power, the artists were given the order to portray the Soviet regime in a good way and therefore they were restricted from freely expressing themselves in their artworks. They were forced to lie and create an illusion of the cruel reality,” she added.

One highlight of the exhibition is that visitors will be able to discover sculptor Vakhtang Kotetishvili. “He is known to society as a splendid writer, but he is less known as a sculptor,” Kiknadze told us. “His wooden statue of a man on his knees represents a symbol of that epoch and people persecuted and oppressed by the totalitarian rule. We chose his sculpture as the main hero of the exhibition, since whereas all the artists in 1930s were ordered to paint happy Soviet citizens and countries, Kotetishvili dared to carve a statue of a man on his knees, demonstrating a devastated and unhappy man living in the Soviet Union.”

All five artists presented on the first floor are exceptional personalities who contributed to Georgian culture. Dimitri Shevardnadze is the founder of the National Gallery of Georgia, having himself collected almost all the artworks by Niko Pirosmanashvili (Pirosmani). He also actively took part in establishing the Tbilisi Academy of Arts with Henryk Hryniewski. Shevardnadze also founded a program of museum management in Georgia and was both initiator and participant of the cultural life of Georgia in the 1920-30s.

Yet another victim and important personality whose bold and cutting-edge artworks are presented at the venue is Petre Otskheli, recognized as a modernist and one of the most progressive artists of his time, not only in Georgia but internationally.

“The second part of the display showcases how artists were influenced by the totalitarian regime and shows the contrast between their paintings, before the occupation and after it. This can be clearly seen in famous Georgian artist Elene Akhvlediani’s two works, the first painted in the 1920s in a free manner, where the artist’s style and signature is visible, while the second artwork, named ‘Abastumi Resort’ was made in 1940 on order,” Kiknadze said. “At that time, Soviet censorship approved and supported only naturalist paintings. At the venue, one can see examples of Soviet censorship and the artworks that were criticized or prohibited due to their distinctiveness. At the time, jury members instead of art critiques, representatives of the Communist Workers’ Party, evaluated the paintings not from an artistic or aesthetic point of view but based on how it coincided with Soviet ideology.”

The exhibition is on at the GNM on Rustaveli Avenue until March 1.

By Lika Chigladze