Although photography only really had its start in the first decades of the 19th century, and soon after that reached Georgia, writing about this country of course began much earlier. What actual photographic images could not in those earlier centuries convey was either vividly described, or shown through printed versions of paintings in mono or color or in line-based engravings. The photographs came later, but the words did their job to portray Georgia as interestingly as was necessary to capture the imaginations of people seeking new lands to discover without or before going there themselves.

(Often, it must be noted, the writers moved around a Caucasus which had rather different borders from those it has today, with parts of it in Russia proper, others in the Ottoman or Persian Empires. But the communities they wrote about mostly retain the same names, and we know where they were. And they traveled widely, nearly matching their visual counterparts for range and altitude. We cannot only note those which stayed in Georgia: which Georgia, that of the 19th century borders, themselves changing, or within the borders we know today? In any case, a complete 19th century Caucasus bibliography in English, even excluding translations from other languages, is far beyond the scope of this article, which can only whet the reader’s appetite and encourage a search for more if desired.)

Alexandre Dumas (1802-70)

Alexandre Dumas (1802-70)

The most famous chiefly 19th century writer whose works include the Caucasus and Georgia was also one of the most famous of his time in general: Alexandre Dumas (1802-70), French, also suffixed père as he was the father of a namesake writer suffixed fils. Best known for novels The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, he also wrote considerable nonfiction and travel accounts, including the one which we note here, Voyage to the Caucasus (1858-9). Unfortunately, less than half of this book is available yet in English, as Adventures in the Caucasus; so we must wait and hope.

Arnold Zisserman’s Twenty-Five Years in the Caucasus, 1842-1867, is available from Narikala Press, Tbilisi, in 2 volumes, illustrated. This English translation has undergone much necessary editing and improvement from the original Russian, and the work covers much history of a time when the region was experiencing much change, as wars and political movements swept across it. Zisserman was only 17 when he arrived, and he saw and experienced much here.

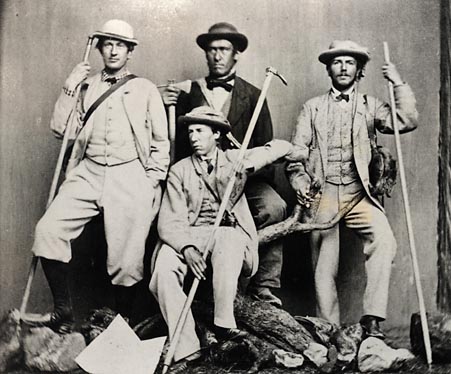

The Exploration of the Caucasus (1896 & after), by the Royal Geographic Society’s Douglas Freshfield, had the benefit of handsome photographic illustrations by none other than Vittorio Sella, so, a most sought-after pairing in the original 2 volumes, which are quite expensive to obtain. Much high-mountain ground was being covered and described in English for the first time then.

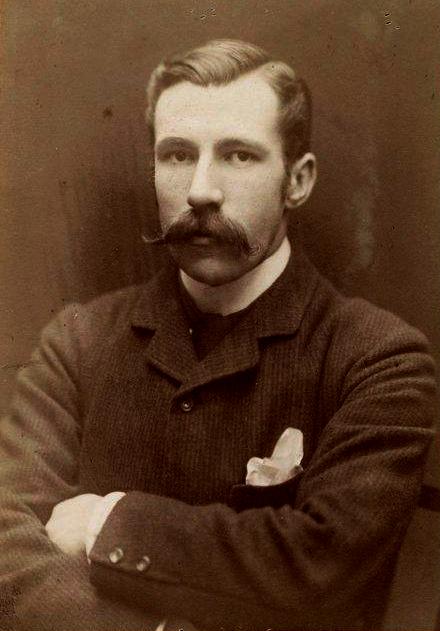

Savage Svanetia (1883, 2 vols. and 1-vol. version) by Clive Phillipps-Wolley (1853-1918) concentrates on Svaneti, of course. He was a British-born Canadian traveler, writer and enthusiastic hunter of considerable popularity at his height, enjoying comparisons to Kipling for the energy, freshness and vigor of his writing. Herein he refers to Svaneti that it had "always been spoke of to me as a hungry land inhabited by an angry people." How much of that is true today?

Clive Phillipps-Wolley (1853-1918)

One thing becomes clear as you delve into writings about the Caucasus from eras past is that you must learn to read between the lines, and to deal with the thoughts and prejudices of the authors and their times. There is still much of value to be found in these and so many other books of local interest, while many other such books still await translation and printing, for which the main issue is of course funding of a risky venture which will hopefully repay the outlay and then some. From originals in Russian, German, French, Turkish, Persian, Arabic and other languages, we too wait to see what has been expressed in millions of words over many centuries. Add local languages, Georgian, Armenian, Azeri and nearly 50 smaller ones, and the treasure trove becomes almost too large to imagine, let alone to try to take in and learn from.

The Caucasus is too rich a location to sum up simply, especially with the sheer amount of huge change it has seen across millennia. Peoples, archeology, cultures, cuisines, histories, languages, customs, events, wars, religions, mythologies, even just alphabets (the Abkhaz language has seen about 7 of these attempted for it over 3 centuries)… whatever your interest, the Caucasus version has had details written describing it to reward your search and perusal. If building even an electronic library of the whole thing in any one major language is too much, at least one can make a start, make discoveries and find answers to the questions of what, when, and simply why or how. Living or just visiting here, we owe it to ourselves to try to learn and come away richer, to try to understand. The words others have left behind will help us achieve this, making sense of such a fascinating region.

I also refer the literary explorer to the blog Georgia Through Foreign Eyes, http://foreigners-georgia.blogspot.com/ which begins in antiquity and goes through the 20th century. Much useful material here!

Douglas Freshfield (front, center)

"A mountain Prince once offered me a lease of all the minerals, and the exclusive right of keeping hotels, in his territory, on certain conditions. A company promoter might find an opening even in Suanetia, but I should be sorry to promise his shareholders that they will make their fortunes." (Douglas Freshfield)

"There is no greater insult to an Ossete than to tell him that 'his dead are hungry'!" (Douglas Freshfield)

"The maize was ripe in the fields, and the bears on the neighbouring hills were only to be restrained from their favourite food by the whole force of the male population." (Douglas Freshfield, on Svaneti)

"Farther to the right stand two great rock-towers, linked, like those of a Gothic cathedral, by a lofty screen. These are Ushba, the Storm-peak, the tutelary mountain of Suanetia." (Douglas Freshfield)

"The fathers of these men had nearly murdered us twenty years before : with my present companions I had nothing but pleasant dealings, and it was with regret we saw their bright faces and dark turbans disappear for the last time as they rode off home." (Douglas Freshfield, on Svaneti)

"All day long Vassili kept croaking about the weather. A snake, he said, had bitten the moon last night, which accounted for its having turned blood red before it set, and presaged bad weather to come." (Clive Phillipps-Wolley)

"A young Svtin begins life early, and has to make himself of use almost as soon as he can talk." (Clive Phillipps-Wolley)

"Now, as I looked from the balcony across the patches where the uncut crops still stood, the snow fell thick and fast ; and though it was only the 18th of September, all the country was already white with the first fall of winter." (Clive Phillipps-Wolley, in Ushguli)

"If ever I travel through Svanetia again, I am resolved that though a horse may carry my packs, no legs but my own shall be trusted to carry my person." (Clive Phillipps-Wolley)

"The Khevsurs consider every European to be a healer, and sugar to be the best cure for all diseases." (Arnold Zisserman)

"Mestia alone has seventy to eighty towers 40 to 80 feet high, Ushkul about fifty, and two castles besides." (Douglas Freshfield)

***

Tony Hanmer has lived in Georgia since 1999, in Svaneti since 2007, and been a weekly writer and photographer for Georgia Today since early 2011. He runs the “Svaneti Renaissance” Facebook group, now with nearly 2000 members, at www.facebook.com/groups/SvanetiRenaissance/

He and his wife also run their own guest house in Etseri: